The Mahalchhari Incident: Meghna Guhathakurta

![]()

On 24 August 2003, Rupom Mohajon, a settled Bengali resident of Babupara, was abducted and a demand for ransom was made. Local Bengali businessmen held meetings in the Babupara Bazaar demanding Rupom’s immediate release. That meeting, held under the leadership of the local BNP leader Dewan Abul Kalam Azad and the banner of the ‘Bengali Shommonoy Parishad’ (Bengali Coordination Council), announced a strike and road blockade the next day. Later that afternoon, some of the businessmen apprehended the Chairman of Shindukchori Union Porishod, and beat him and held him overnight against his will. By 26 August, a group of Bengalis assembled in the Bazaar area, and began to harass the Paharis who had come there to sell their wares, chasing them out. By this time, a number of soldiers had also joined them from the Army camp near the Bazaar. Several of the Bengalis attacked Binod Bihari Khisha, a former Union Parishad Chairman, with lathis (cane) as he sat in his shop. He was later taken to the Army Camp near the Bazaar, where he died. Several other Paharis were also assaulted.

The army allegedly bayoneted Nidorshon Khisha, son of Binod Bihari Khisha, as he stood near his father. Another Pahari boy of Babupara, was also beaten while in custody at the Army camp situated between Babupara and Mahalchari Bazaar.

The assembled Bengalis, accompanied by soldiers of the 21st East Bengal Regiment, then went into Babupara village. They looted the houses, poured petrol and kerosene onto them, setting them alight as they went. They also looted and set alight a private Buddhist temple in Babupara. From there, they proceeded to Rameshu Karbari Para and Saw Mill Para, again settling light to houses and looting them as they went. They then proceeded in engine-powered boats to several other villages. In addition to burning and looting houses, they assaulted several women and girls. The mob then swept into Tholipara, Kerengyanal and Durpojyanal. In each village, they looted houses, and then set them alight. In Kerengyanal village, several women were raped or sexually assaulted, an infant was killed. Later that day, Paharis in Lemuchori and Noapara villages, to the north and on the road to Khagrachari, were attacked by a group of Bengali settlers from a nearby cluster village, Chongrachori. A Buddhist temple and several houses and shops were looted and torched. Several Paharis reported that these incidents occurred within a short time after the local MP, Abdul Wadud Bhuiyan, had travelled through the area en route to Mahalchhari, and that he had incited the local

Bengalis to instigate this particular attack.

The persistence of militarization

During the period of ‘insurgency’, the CHT underwent total militarization. The army divided the region into three zones: white, green and red. The white zones, considered ‘neutral’, covered an area two miles adjacent to the Army Head Quarters and were jointly populated by Bengali settlers and Hill people. The green zones were the Bengali settlement areas. The red zones were the areas in the interior of forests populated by only Hill people where the military carried out its counter insurgency operations. In the name of counter insurgency, human rights violations included extra-judicial killings, torture, abduction, religious persecution, forced eviction, destruction of homes and properties, and wide-scale arrests and detention. There were eleven massacres of Hill people, the most known being at Longodu, Logang and Naniarchar. Although inquiry commissions and other investigative processes were initiated following public protests, none of their findings ever saw the light of day. The military continued to enjoy impunity regarding allegations of human rights violations. The very limited withdrawal of the military camps (according to one source only 35 of the estimated 520 military are reported to have been dismantled) had contributed to the persistence of military hegemony in the region.

The politics of vote

At the time of the Accord, all three MPs of the region were from the then ruling Awami League and were of the indigenous population. In the first election since the Accord, in October 2001, a major upset occurred when the PCJSS, protesting the inclusion of non-permanent residents of the region as voters, withdrew from the polls. This factor, together with the UPDF’s decision to contest the Khagrachari seat, split the vote of the indigenous people and threw open the door for BNP candidate Abdul Wadud Bhuiyan, himself a Bengali settler, to be voted in, predominantly by the Bengali settler population. As a consequence of his victory, Bhuiyan had become the first Bengali person to be an MP from the CHT. He also became the chairperson of the CHT Development Board, which has access to significant amounts of development funds. Government sponsored settlers in the CHT have therefore consolidated their position vis-a-vis the indigenous people, more so since they are no longer threatened by an active guerrilla force. Many of them rally around the banner of the BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami, and have been vocal critics of the CHT Accord, alleging that it subjects them to discrimination vis-a-vis the Paharis.

The non-resolution of the settler issue

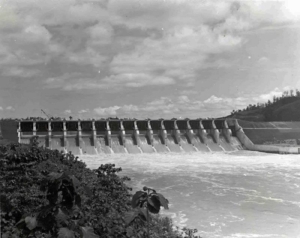

The success of the CHT peace process is dependent largely upon the resolution of land–related issues, which has been complicated by: (a) government sponsored settlements used as a counterinsurgency measure; and (b) the different perception of land and land ownership between Bengalis and hill people. In a land hungry situation with 0.29 acres per capita land in Bangladesh, the settlements proved popular with Bengalis, many of whom were themselves landless. But this myth of the “emptiness” of the CHT, compared to high density of population in the plainlands and the idea that Bengalis were settled in Government owned khas land, was seriously misconstrued. Research has established that the area of cultivable land in the Hills is very small. Only 3.2 % of CHT land was suitable for all purpose agriculture (A category land) while 15% was suitable for forestry and fruit gardens (B category land) and 77% suitable only for afforestation. More importantly, what the Government of Bangladesh calls ‘khas’ land is understood by the Hill people to be common land or land, which they use for traditional jhum (swidden) cultivation and forests.

A post-accord watershed

The Mohalchori incident was a watershed in the sense that this was the first time after the Accord that such an incident had taken place at such a large scale. The widespread extent of arson in all affected villages resulted in the burning and destruction of the majority of houses belonging to Hill people, as well as the incineration of coconut trees and water pumps. The incident caused thousands of people to be displaced from their homes and villages. The threat of false cases issued against those hill people who dared to protest means that a reign of terror continues to prevail across the area. This is effectively preventing young men( falsely implicated in cases) from returning home.

(1) Occupation of land: Many people in the affected villages were concerned and anxious that the ultimate effect of such incidents would be the occupation of the Hill people’s land. Since their economic activity had been worst hit by this incident, many people would be forced to sell their lands at cheap prices or mortgage them in order to survive.

(2) Economic power targeted: Many of the villages affected are in low-lying land surrounded by the Chengi river, which is rich in fish and marine resources. Since Bengalis are generally considered to be skilful in fishing, the villagers think that Bengalis are anxious to occupy these lands on the waterfront. The villages are also in an area which produces only one Boro rice crop. Irrigation is therefore considered essential. The targeting of irrigation pumps in the richer households had caused deep uncertainty for the ensuing agricultural season.

(3) Divide and rule: Several Paharis told us that the Bengali Hindu households were considered to be ‘old settlers’ and therefore distinct from the predominantly Muslim settler population of the eighties. But in this incident the rioters and armed forces created a division between the Bengali Hindus and the Hill people. In Babupara, all the houses of the Hill people were burnt, and the only ones left standing were the three to four houses belonging to Bengali Hindus.

(4) Sexuality as an instrument of terror: Sexual aggression, which may culminate in rape, has been a common feature in incidents of community and state violence in South Asia. Women with whom we talked described their desperation as they were chased into the water and the jungle, their daughters hit by sharp instruments, their mothers beaten by heavy sticks. Many of these young women are afraid to come in front of strangers, especially Bengalis. Their participation in schools has decreased and their studies affected.

(5) Internal displacement and rehabilitation: Arson attacks of massive proportions made hundreds of people homeless and dislocated. Kerengyanala village was the furthest from Mahalchhari Thana and not a single house had been built for them by any authority since the

incident. Other villages which are closer to Mahalchhori Thana and to the local Army Camp by Babupara Bazaar, including Babupara, or Saw Mill Para, now sport a number of newly constructed one-room bamboo huts with tin roofs which the Army had built for the affected people. In many cases, these huts were much smaller than the original homesteads which had been burnt down during the arson attack. People told us that they had heard that there was a 30 lakh taka budget sanctioned for this but that it had all finished. Others mentioned that UNDP officers had come to take measurements of their previous homesteads and that they expected that there would be further construction. Some of the affected families refused to accept the huts offered to them as it was much less than what was lost.

(6) Strengthening settler vote banks for the future: The politics of the vote bank had so far been used in Bangladesh to intimidate one’s opponent’s voters to the extent required to ensure one’s own power base as well as enjoy the resources left behind. This had been the case during the national elections of October 2001 where Hindu voters in Hindu-concentrated areas of the south-west and the south had been threatened and put under heavy pressure by the BNP-led coalition to not to go to the polling booths since they were considered ardent voters of the Awami League. The dark side of electoral democracy, which had manifested itself in the election of October 2001, may just be making

its way into the Hills too, thereby creating its own dynamics.

Abbreviated from ” Ethnic Conflict in a Post-Accord Situation: the Case of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh”, presented at conference organized by the Dept. of Sociology, University of Mumbai,

March 3 to 5, 2004.