Structural Roots of Violence in CHT: Bhumitra Chakma

![]()

A regional political party – Parbatya Chattagram Jana Sanghati Samiti (PCJSS) (United Peoples Organization of the Chittagong Hill Tracts), was formed in the early 1970s in reaction to GoB’s assimilationist policy. In the 1973 general elections, the PCJSS candidate, M.N. Larma, was elected to represent the CHT people in the national parliament. In parliament, he repeatedly demanded constitutional recognition of the separate identities of the indigenous communities. When the demand went unheeded, the PCJSS organised a guerrilla force, Shanti Bahini (Peace Force), in the mid-1970s to pursue regional autonomy. Armed clashes soon ensued between this Shanti Bahini and the Bangladesh armed forces that continued till the signing of a peace accord in December 1997. In the interim years, violence took structural root in the CHT.

Militarisation and Massacres

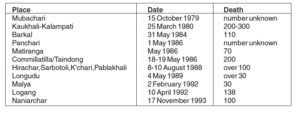

As soon as armed clashes began, GoB militarised the region by deploying 115,000 military personnel – one soldier for five to six hill persons (Levene 1999: 354). In the 1980s, the CHT was, effectively, turned into a large military garrison. As a result of this militarisation of the region, attack on indigenous villages and detention, torture, disappearance and killing of the Hill People became almost routine occurrences. From the late 1970s onward, the armed forces also started massacre as a policy instrument. On 15 October 1979, government forces massacred unarmed villagers in Mubachari, the first large scale killing in the CHT (Samad 1980), and Amnesty International reported more such massacres in the subsequent years committed jointly by the military and the Bengali settlers (Amnesty International 1986). The Kaukhali massacre on 25 March 1980 (ironically it was on this day that Pakistani forces had first attacked unarmed Bengalis in 1) surpassed, according to Chittagong University academic Hayat Hossein (1986), “all previous records of brutalities” committed against indigenous people. This was confirmed by fact-finding team of Upendra Lal Chakma, Shahjahan Siraj, and Rashed Khan Menon. The consistent pattern of these massacres in

the 1970s and 1980s were the crossing of the Rubicon from a “genocidal process” to “active genocide” (Levene 1999: 359).

Policy of Demographic Change

From the late 1970s, the Bangladeshi government has consistently pursued a policy of “change the demography” in the CHT. The only objective of this policy appears to be to outnumber the indigenous people in their own land. Eviction from their homes and lands, and massacres were the most prominent measures of this broad approach pursued by the armed forces in collusion with the Bengali settlers.

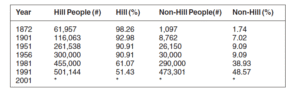

From this period, the government began to settle Bengalis in the CHT and planned to provide five acres of hilly land, four acres of mixed land and 2.5 acres of paddy land to each settler family (Anti-Slavery Society 1984: 71-73). How vigorously the government pursued the policy can be observed in the rapid change of the CHT’s demographic structure. The following table highlights this:

CHT Population: Hill and non-Hill People (1872-Present)

*Curiously the 2001 Census does not provide a figure categorising hill people and Bengalis in the CHT.

The Bengali settlement programme not only quickly altered the demographic character of the CHT, it also expedited the process of ethnic cleansing. Indeed, ethnic cleansing was ingrained in the GoB’s policy, because without evicting the indigenous people from their lands it was simply not possible to settle Bengalis in the CHT. Between 1980 and early 1984, according to The Guardian (March 6,1984), 400,000 Bengalis were settled in the CHT. Assuming 4 persons in a family, it means that about 100,000 families were brought during this period. If each family was to be given 5 acres of hilly land, 4 acres of “mixed” land and 2.5 acres of paddy land as planned, then following amounts of land were

necessary:

Hilly land: 100,000X5 acres = 500,000 acres

“Mixed” land: 100,000X4 acres = 400,000 acres

Paddy land: 100,000X2.5 acres = 250,000 acres

But the trouble was that the amount of land that was necessary to settle the new immigrants was simply unavailable in the CHT, as Shapan Adnan’s research shows. Bengali settlement continued after 1984 and indeed continues till date. The government brought Bengalis for settlement in the CHT in large numbers but certainly could not provide the amount of land it promised to each settler family because of unavailability of cultivable land. Hence, what the settlers simply did was that they began to grab the lands of the indigenous people (for details on this, see Roy 1997: 167-208; Adnan 2004). And in this effort they got active support from the Bangladesh armed forces. Eviction, terrorization and massacres in the CHT were part of this process. In the 1980s, terrorization led about 50,000 indigenous people to become refugees in India and Bengali settlers grabbed the lands left by them. Put simply, without grabbing the lands of the indigenous people it was not possible to settle any outsider in the CHT.

The intermittent eruption of violence in the CHT is the direct result of GoB’s policy of Bengali settlement. It is now structurally ingrained. Unless this structural root of violence is addressed it is unlikely that durable peace will return to the CHT. A peace accord was signed between the GoB and the PCJSS in December 1997. In the last 13 years this accord has not delivered the intended peace in the CHT. Rather violence has reappeared continuously in the region. One of the key reasons for this is that the accord failed to address the structural cause of the problem in the CHT – settlement of Bengalis and their usurpation of indigenous land. Without addressing this, it is a simple equation that the peace accord will not only falter; the CHT will experience more violence and bloodshed in the years to come. And the process of ethnocide will continue.

References

ACHR (Asian Centre for Human Rights) (2010): Bangladesh: IPS Massacred for Land Grab, 23 February; accessed at:

http://www.achrweb.org/reports/bangla/CHT012010.pdf

Adnan, S. (2004): Migration, Land Alienation and Conflict: Causes of Poverty in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh,

Research and Advisory Service, Dhaka.

al-Ahsan, S A and B Chakma (1989): “Problems of National Integration in Bangladesh: The Chittagong Hill Tracts”, Asian

Survey, vol. 29, no. 10, pp. 959-70.

Amnesty International (1986): Bangladesh: Unlawful Killing and Torture in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Amnesty International,

London.

Anti-Slavery Society (1994): The Chittagong Hill Tracts: Militarisation, Oppression, and the Hill Tribe, Anti-Slavery Society

Publication, London.

CHT (Chittagong Hill Tracts) Commission (1997, 2000): Life Is Not Ours: Land and Human Rights in the Chittagong Hill Tracts,

Bangladesh, International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, Copenhagen.

Hossein, H. (1986): “Problem of National Integration in Bangladesh” in Bangladesh: History and Culture, Vol. 1, S R

Chakravarty and V Narain (ed.) (New Delhi: South Asia Publishers).

Levene, M (1999): “The Chittagong Hill Tracts: A Case Study in the Political Economy of ‘Creeping’ Genocide,” Third World

Quarterly, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 339-69.

Ministry of Law (1972): The Constitution of The People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Government of Bangladesh, Dhaka.

Mohsin, A (1999): The Politics of Nationalism: The Case of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh (Dhaka: University Press

Limited).

-(2003): The Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh: On the Difficult Road to Peace (London: Lynne Rienner).

Roy, R D (1997): “The Population Transfer Programme of 1980s and the Land Rights of the Indigenous Peoples of the

Chittagong Hill Tracts” in Living on the Edge: Essays on the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Subir Bhaumik, Meghna

Guhathakurtha and Sabbyachasi Basu Ray Chaudhury (ed.), Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata, pp. 167-208.

Samad, S (1980): “What is Happening in the Chittagong Hill Tracts?” (in Bengali), Robbar, 22 June.

*Dr. Bhumitra Chakma is Senior Lecturer and Director of the South Asia Project in the School of Politics & International Studies at the University of Hull (UK).

Published in Economic & Political Weekly, India, March 20th, 2010.