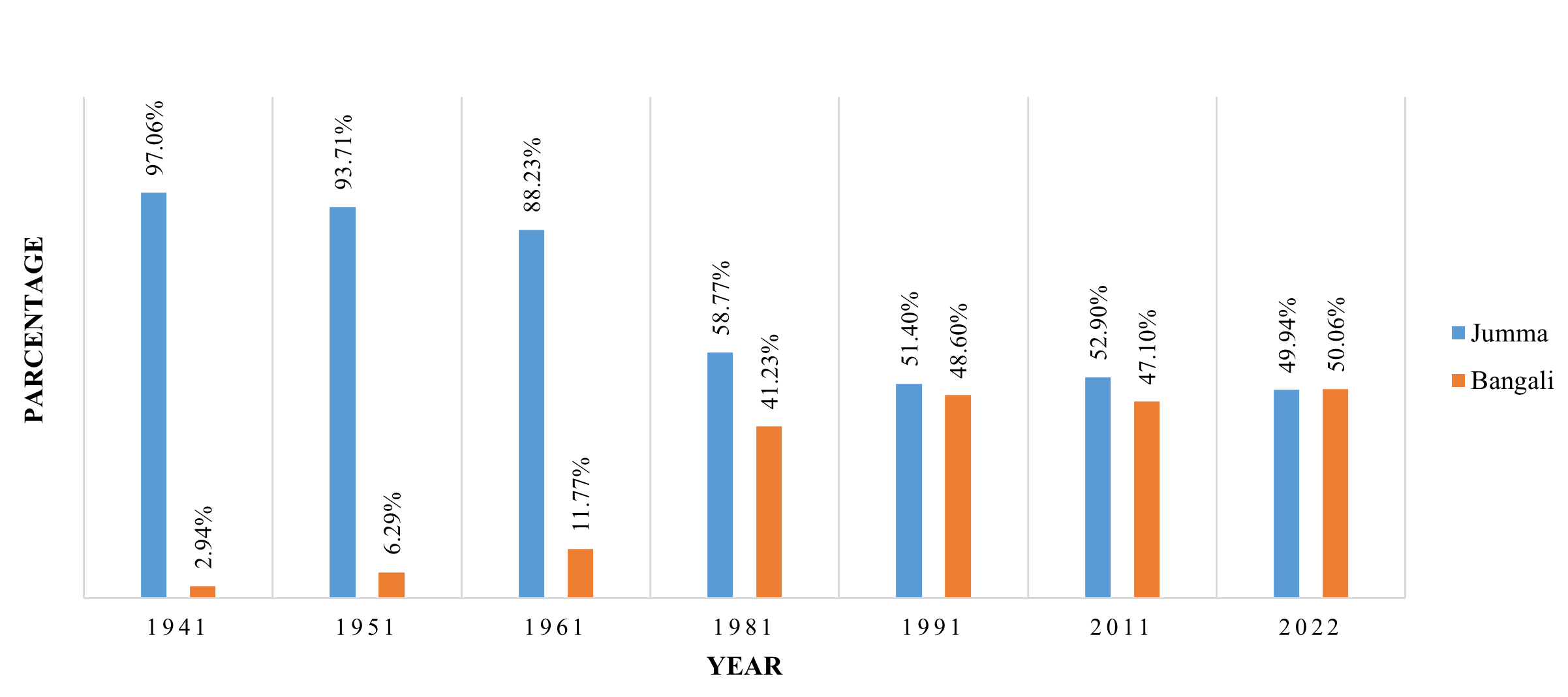

Population ratio between the Jumma and Bangali in the CHT

![]()

Graph: Population ratio between the Jumma and Bangali in the CHT

Source: BBS

The graph illustrates the demographic transformation between the Jumma and Bengali populations from 1941 to 2022. In 1941, the Jumma community made up an overwhelming majority at 97.06%, while the Bengali population was only 2.94%. Over the following decades, the proportion of Jumma steadily declined, dropping to 93.71% in 1951, 88.23% in 1961, and sharply to 58.77% by 1981. In contrast, the Bengali share rose consistently, reaching 41.23% by 1981. By 1991, the two groups were nearly balanced, with Jumma at 51.40% and Bengali at 48.60%. The trend of near parity continued in 2011, with Jumma at 52.90% and Bengali at 47.10%. However, in 2022, a pivotal shift occurred as the Bengali population surpassed the Jumma for the first time, with 50.06% compared to 49.94%. Overall, the chart highlights a dramatic demographic shift over eight decades, showing the steady decline of the Jumma majority alongside the continuous rise of the Bengali population, ultimately leading to a reversal of majority status.

The dramatic decline of the Jumma population and the rise of the Bengali population can largely be explained by historical, political, and socio-economic factors rather than natural demographic change alone. Following the partition of India in 1947 and later the creation of Bangladesh in 1971, state-led migration and settlement programs encouraged large numbers of Bengalis to move into the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT), traditionally inhabited by Jumma indigenous communities. The construction of the Kaptai Dam in the 1960s also displaced tens of thousands of Jumma people, forcing many to migrate to India and Myanmar, further reducing their share in the region. Over time, government-sponsored land distribution, military presence, and the promise of fertile land for Bengali settlers accelerated demographic replacement. These policies were often tied to national integration strategies, where settling Bengalis in the hills was seen as a way to secure territorial control and assimilate minority groups. The result was not only a demographic inversion but also long-standing land disputes, cultural erosion, and tensions between the Jumma and Bengali populations that continue to shape the region’s socio-political landscape today.